Markets are catching their breath after the trade truce between Washington and Beijing but the calm is disguising a deeper structural shift.

The deal goes beyond pausing tariffs as it touches export controls, technology dialogue, and supply-chain security. It feels like déjà vu from 2018 and 2019, when tit-for-tat tariffs rattled global supply chains, tech exporters were swiftly re-rated, and resource producers suddenly returned to favour.

Yet the stakes today are much higher. The US is not merely defending its domestic industries. It is securing control over the technologies that will define the next decade, from semiconductors to clean energy.

Meanwhile, China is using its dominance in rare earths and critical materials as strategic leverage over its fellow superpower.

Together, they are reshaping how the world builds, trades, and invests. It’s also a stark reminder for investors that geopolitical risk has returned as a permanent variable in how the market values risk.

Key Points

- The new phase of US–China trade tensions is shifting from tariffs to control over semiconductors, rare earths, and critical supply chains.

- Capital is rotating toward resource producers and diversified manufacturing hubs as companies move away from China-centric production models.

- Rising geopolitical risk is reshaping currencies, commodities, and sector leadership, market participants have historically favoured firms with resilient sourcing and supply-chain flexibility, based on observed trends rather than guaranteed outcomes.

Revisiting 2018–2019: The First Wave

The first wave of the US–China trade conflict that began in 2018 was about more than tariffs. In its first year, the US imposed duties on more than US$300 billion worth of Chinese imports, and by late 2019, that number had risen to roughly US$350 billion.

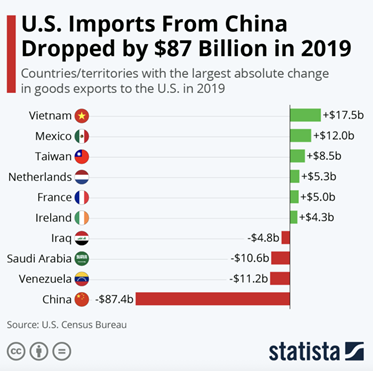

Back then, it was much more about physically-manufactured goods. The consequences for global supply chains were immediate. US imports from China fell by nearly US$87 billion between 2018 and 2019, the sharpest annual decline in US trade outside the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) at that time [1].

Manufacturing hubs began to migrate not just because costs were climbing but because companies realised how dependent they had become on China for components, logistics, and assembly.

A World Bank study found that China’s share of US imports dropped from 22% to 16%, with production shifting to Vietnam, Mexico, and other emerging hubs [2].

What followed was a fundamental rethink of global business strategy. The old playbook of chasing the lowest production cost and shipping goods worldwide gave way to a new focus on building resilient and diversified supply chains.

Multinationals began spreading their production across multiple countries, shortening supply lines, and securing critical inputs closer to end markets. Investors started rewarding companies with visibility into their sourcing networks and penalising those that were overly reliant on a single geography (typically China).

The 2018–2019 trade episode redefined how the market priced geopolitical risk, and laid the groundwork for today’s renewed rotation.

What’s Different This Time?

The last trade war was about tariffs and retaliation. This one is about control. The battleground has shifted from finished goods to the foundational technologies and materials that power them.

Semiconductors, electric vehicles, renewable-energy infrastructure, and rare-earth minerals now sit at the heart of the competition. China still refines roughly 70% of the world’s rare earths and dominates the processing of critical minerals used in magnets, batteries, and chips.

Export-licensing regimes are tightening, and the US is simultaneously subsidising domestic chip fabrication and encouraging allies to localise production. The structure of global trade is being slowly rewritten.

Related Reads: Tariffs, Talks, and Tension Can the US–China Trade Truce Hold in 2025

Winners and Losers of the New Trade Order

The result is a rotation that goes beyond tariffs. Capital is shifting from companies that depend on China-centric manufacturing to those that control key inputs or alternative production routes.

Rare-earth producers such as Lynas Rare Earths, MP Materials, and Arafura Resources are increasingly viewed not just as miners but as strategic enablers in the clean-energy and EV ecosystem.

Their dominance in elements like neodymium and praseodymium gives them pricing power and relevance in a world that prizes supply assurance over pure cost efficiency.

Meanwhile, nations such as Malaysia, Australia, and Indonesia are becoming part of a new supply corridor linking mining, refining, and downstream processing outside China. Malaysia’s new neodymium-magnet project, developed by Lynas and JS Link, reflects a “mine-to-magnet” integration model that reduces exposure to Chinese processing.

Elsewhere, Japan’s Proterial and Shin-Etsu Chemical are expanding magnet-recycling and manufacturing capabilities to support global EV demand.

Semiconductor players like TSMC and Amkor are diversifying their footprint across the US, Vietnam, and Malaysia, while electronics manufacturers such as Jabil and Flex are strengthening operations in Mexico to be closer to North American markets.

These shifts are not temporary hedges but structural realignments. They redefine how and where capital flows, from growth-at-any-cost toward strategic resilience. Resource-rich economies are emerging as beneficiaries.

Australia’s critical-minerals ecosystem and Canada’s battery-metal sector are attracting heavy Western investment, while Southeast Asia positions itself as the middle node between resource supply and advanced manufacturing.

Remaining Nimble is “Name of the Game”

The other side of the rotation tells a different story. Semiconductor leaders such as NVIDIA, Intel, and Micron remain caught between export controls and rising costs. Each new regulation adds another layer of uncertainty to production schedules and profit margins.

EV makers like Tesla, BYD, and NIO are seeing input costs climb as magnet and battery materials tighten in availability. Technology exporters such as Apple, Dell, and HP, along with contract manufacturers like Foxconn and Pegatron, are facing higher logistics costs and supply delays as they diversify out of China.

Note: Semiconductor leaders such as NVIDIA, Intel, and Micron, and EV makers like Tesla, BYD, and NIO are cited here purely for illustrative purposes to discuss industry trends and supply-chain impacts; this is not a recommendation to buy or sell any instrument.

Related Read: How Tariffs Could Reshape Apple’s Supply Chain and Stock Outlook

At the most vulnerable end of the spectrum are cost-takers in consumer electronics and appliances such as Haier, Hisense, and TPV Technology. These companies operate on thin margins and have little pricing flexibility, forcing them to absorb higher component costs themselves.

The result is a new performance map. Capital is flowing toward the parts of the market that control resources and offer supply security, while those that rely heavily on low-cost, China-centric production are under pressure to adapt.

How It Might Play Out for Investors

Market participants may take note of companies that secure multiple sources of input, localise production, and maintain control over their value chain.

In this new era of trade, companies focusing on resilience may be better positioned to navigate volatility.

Aside from that, the currency and commodity markets are also affected by this shift. The Chinese yuan has been guided lower amid signs of weakening industrial competitiveness and export risk.

At the same time, the Australian dollar has strengthened, backed by the mining-sector rally and higher resource export incomes. Commodity prices themselves are being repriced not simply on demand but on supply-security.

Industrial metals such as copper, nickel, aluminium, and especially rare earth-related minerals, are increasingly trading on geopolitical risk premiums rather than traditional consumption cycles.

Relief But Not Resolution

The Trump–Xi truce offers a brief respite, but it is not a return to normalcy. The handshake signals a transition from open conflict to managed rivalry. Tariffs may have been trimmed, yet export-controls, technology bans, and localisation mandates remain unresolved.

The underlying currents, such as strategic decoupling, investment in domestic capacity, and hedging of geopolitical exposure, continue to drive capital allocation decisions.

For companies, this means the trade war has evolved into a supply-chain redesign that is unlikely to reverse even if diplomacy improves.

Volatility and Opportunity

Periods of structural change are both disruptive and fertile. Investors who understand where resilience meets growth will find opportunity amid volatility.

Over the next decade, companies with diversified sourcing, transparent logistics, and control over essential materials may be better positioned . Those still locked into China-centric supply chains face margin compression and valuation downgrades.

A useful way to think about this is through contrast. Consider two semiconductor firms. One still sources the majority of its inputs from Mainland China. The other has relocated production to Malaysia and the US.

Under a new wave of export-controls or tariffs, the first could see margins evaporate, while the second may retain stability and even gain market share. This divergence in resilience is what markets are beginning to price in.

The same principle applies to resource producers. Rare-earth miners and magnet manufacturers are no longer speculative side bets.

They are becoming the backbone of an industrial strategy that blends technology, national security, and sustainability. Currencies and commodity flows will continue to act as real-time indicators of where global manufacturing power is migrating.

Bottom Line for Investors

This tariff-driven rotation marks more than a market adjustment. It signals a structural turning point in how trade, technology, and policy converge. And it’s likely to be a shift that plays out over the next five to 10 years.

The next phase of global investing may favour companies that can endure and adapt when conditions shift. The real edge now lies in foresight and the ability to rewire supply chains, secure inputs, and anticipate regulatory change before it hits the bottom line.

Growth still drives valuation, but resilience has become the new measure of strength. As we move into the second half of 2025, market participants may consider whether portfolios are positioned to balance expansion and risk management.

References

- “China – United States International Trade Commission”. https://www.usitc.gov/research_and_analysis/trade_shifts_2019/china.htm . Accessed 26 Nov 2025.

- “Is US Trade Policy Reshaping Global Supply Chains? – World Bank Group”. https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/099812010312311610/pdf/IDU0938e50fe0608704ef70b7d005cda58b5af0d.pdf . Accessed 26 Nov 2025.